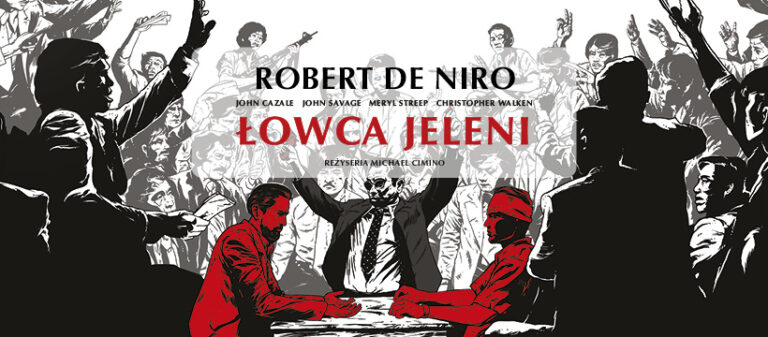

„Łowca jeleni” Michaela Cimino to jeden z najważniejszych i wywołujących najbardziej żarliwe dyskusje tytułów w dziejach kina. Laureat pięciu Oscarów, w tym za najlepszy film, najlepszą reżyserię oraz najlepszą drugoplanową rolę męską. To pełna rozmachu, a zarazem zaskakująco intymna opowieść o przyjaźni, lojalności i cenie, jaką płaci się za dojrzewanie w cieniu historii.

W niewielkim górniczym miasteczku w Pensylwanii trzej nierozłączni przyjaciele – Michael (Robert De Niro), Nick (Christopher Walken) i Steven (John Savage) – pracują w hucie. Wieczorami spotykają się w barze i jeżdżą razem na polowania, ciesząc się prostym życiem. Ich codzienność, z pozoru zwyczajna, nabiera tragicznej głębi, gdy zostają powołani do wojska i wysłani – tuż po hucznym ślubie Stevena – na wojnę w Wietnamie.

Cimino z niezwykłą precyzją buduje świat, w którym wielu widzów może się przejrzeć, a potem krok po kroku go burzy – raz w huku wystrzałów i wybuchów, a innym razem w ciszy, w której walka z powracającymi traumami wydaje się skazana na porażkę. W „Łowcy jeleni” zderzenie ludzkiej lojalności z bezsensem wojny ma wymiar nie tylko dramatyczny, lecz także uniwersalny. To historia o przyjaźni wystawionej na najtrudniejszą próbę, o granicach odwagi, o miłości, która nie wszystko jest w stanie ocalić, i o tym, że czasem jeden moment zmienia wszystko.

Tego filmu nie da się zapomnieć.

"André Rieu. Wesołych Świąt!" - Najnowszy koncert bożonarodzeniowo-noworoczny

Zobacz z najbliższymi nowy bożonarodzeniowo-noworoczny koncert André Rieu i jego Orkiestry Johanna Straussa! Najnowsze kinowe widowisko króla walca nosi tytuł „Wesołych Świąt!” i przeniesie Was w prawdziwie magiczny świat świątecznej muzyki i radości. Usłyszycie najpiękniejsze kolędy, cudowne walce i polki oraz bożonarodzeniowe hity. A Emma Kok zaśpiewa dla Was „Mam tę moc” z filmu „Kraina lodu”. To wszystko i inne muzyczne niespodzianki rozgrzeją Wasze serca i wprowadzą Was w atmosferę Bożego Narodzenia oraz Nowego Roku.

Boże Narodzenie i Nowy Rok od zawsze były ulubionym czasem André. Nic więc dziwnego, że z ogromną radością dzieli się on co roku swoim wyjątkowym świątecznym show, nie tylko z publicznością, która na żywo podziwia jego grudniowe występy w Maastricht, ale także z widzami zgromadzonymi w kinach całego świata. To sprawia, że jego świąteczne koncerty ogląda milionowa publiczność.

Maestro wraz ze swoją fenomenalną Orkiestrą Johanna Straussa jak zawsze przygotował widowisko pełne ciepła, śmiechu i emocji. Wśród zaproszonych gości znalazła się fenomenalna Emma Kok, która już podbiła serca publiczności na całym świecie. Na estradę zaś wkroczy 400-osobowa orkiestra dęta, która wykona tradycyjną pieśń „Go Tell It on the Mountain”. Muzycy ci także wesprą swym majestatycznym brzmieniem Annę Reker, która zaśpiewa kolędę „Dzwoneczków dźwięk”.

To coś więcej niż zwykły świąteczny koncert. To pełne muzycznych prezentów i przesycone magiczną atmosferą Bożego Narodzenia kinowe wydarzenie, które na długo pozostanie w pamięci Twojej i Twoich najbliższych.

„Ścieżki życia” to inspirowana prawdziwymi wydarzeniami poruszająca i pełna nadziei opowieść o dojrzałej miłości, która okazuje się silniejsza niż życiowe kryzysy. Film, który zdobył serca widzów w całej Europie, zachwyca szczerością oraz prostotą, z jaką mówi o sprawach najważniejszych. To historia, która podnosi na duchu i przypomina, że nawet po największej burzy można odnaleźć spokój – jeśli idzie się razem.

Raynor (Gillian Anderson) i Moth (Jason Isaacs), małżeństwo z wieloletnim stażem, w jednej chwili tracą niemal wszystko – dom, bezpieczeństwo, dotychczasowe życie. Zamiast się poddać, robią coś, co dla wielu byłoby szaleństwem: wyruszają w pieszą wędrówkę – ponad tysiąc kilometrów wzdłuż dzikiego, angielskiego wybrzeża. Z pustym kontem bankowym, namiotem i garścią najpotrzebniejszych rzeczy idą przed siebie, krok za krokiem, szukając ukojenia w wietrze, ciszy i otaczającej ich przyrodzie. Wkrótce odkryją, że mimo przeszkód, które los rzucił im pod nogi, wciąż mają najważniejsze – siebie nawzajem. Ta niezwykła podróż stanie się dla nich drogą ku wolności, miłości i nowemu początkowi.

„Ścieżki życia” to inspirowana prawdziwymi wydarzeniami poruszająca i pełna nadziei opowieść o dojrzałej miłości, która okazuje się silniejsza niż życiowe kryzysy. Film, który zdobył serca widzów w całej Europie, zachwyca szczerością oraz prostotą, z jaką mówi o sprawach najważniejszych. To historia, która podnosi na duchu i przypomina, że nawet po największej burzy można odnaleźć spokój – jeśli idzie się razem.

Raynor (Gillian Anderson) i Moth (Jason Isaacs), małżeństwo z wieloletnim stażem, w jednej chwili tracą niemal wszystko – dom, bezpieczeństwo, dotychczasowe życie. Zamiast się poddać, robią coś, co dla wielu byłoby szaleństwem: wyruszają w pieszą wędrówkę – ponad tysiąc kilometrów wzdłuż dzikiego, angielskiego wybrzeża. Z pustym kontem bankowym, namiotem i garścią najpotrzebniejszych rzeczy idą przed siebie, krok za krokiem, szukając ukojenia w wietrze, ciszy i otaczającej ich przyrodzie. Wkrótce odkryją, że mimo przeszkód, które los rzucił im pod nogi, wciąż mają najważniejsze – siebie nawzajem. Ta niezwykła podróż stanie się dla nich drogą ku wolności, miłości i nowemu początkowi.