[PL]

Romans Omara, Londyńczyka pakistańskiego pochodzenia (który ma dowieść swej przedsiębiorczości, wyciągając z ruiny jedną z rodzinnych pralni samoobsługowych) i jego kumpla z dzieciństwa, Johnny’ego, dumnego ze swego białego koloru skóry ulicznika sympatyzującego z Frontem Narodowym. A wszystko to na tle ponurej rzeczywistości głębokiego Thatcheryzmu, kiedy rasizm, homofobia i klasizm miały się doskonale. MOJA PIĘKNA PRALNIA to wspólne dzieło reżysera – młodego Stephena Frearsa, który za chwilę miał się stać jednym z najważniejszych brytyjskich filmowców, oraz Hanifa Kureishi, scenarzysty, wówczas u progu wielkiej literackiej kariery. To film przełomowy także dla Daniela Day-Lewisa, wcielającego się w rolę Johnny’ego.

Frears i Kureishi nie boją się kontrowersji. Odwracają zwyczajowy porządek kojarzony z latami 80.: tu przedsiębiorczość jest reprezentowana przez dynamicznych Pakistańczyków, nie angielską klasę średnią. Biali Anglicy zostają natomiast ukazani jako underclass, wyładowująca swoje frustracje w agresji i ulicznych bójkach. Subwersywność filmu idzie dalej, bezlitośnie punktując wszystkie (nawet te pozytywne) stereotypy w postrzeganiu każdej z prezentowanych grup. Bawiąc się konwencją komedii i zgrzebnego realizmu społecznego, twórcy stworzyli dzieło radykalne w swej wymowie, nie oszczędzające nikogo. Jego głównym tematem jest kwestia tożsamości i jej nieoczywistości. Celem – rozbicie sztywnych wyobrażeń oraz pokazanie politycznego wymiaru Inności.

[ENG]

The romance between Omar, a Londoner of Pakistani descent (who has to prove his entrepreneurial spirit by pulling one of his family’s self-service laundries out of ruin) and his childhood pal Johnny, a proudly white streetwalker sympathetic to the National Front. And all of this set against the grim reality of deep Thatcherism, when racism, homophobia and classism were perfectly fine.

MY BEAUTIFUL LAUNDRETTE is a collaborative effort between the director, a young Stephen Frears, who was about to become one of Britain’s most significant filmmakers, and Hanif Kureishi, a screenwriter then on the threshold of a major literary career. It is a landmark film, especially for Daniel Day-Lewis, who portrays the character of Johnny.

Frears and Kureishi are not afraid of controversy. They reverse the usual order associated with the 1980s: here, entrepreneurship is represented by dynamic Pakistanis, not the English middle class. The white English are instead portrayed as underclass, venting their frustrations in aggression and street brawls. The film’s subversiveness goes further, mercilessly scoring all (even the positive ones) stereotypes in the perception of each group presented. Playing with the conventions of comedy and gritty social realism, the filmmakers have created a work that is radical in its message and spares no one. Its main theme revolves around the complexity of identity and its ambiguity, aiming to dismantle rigid perceptions and reveal the political dimension of Otherness.

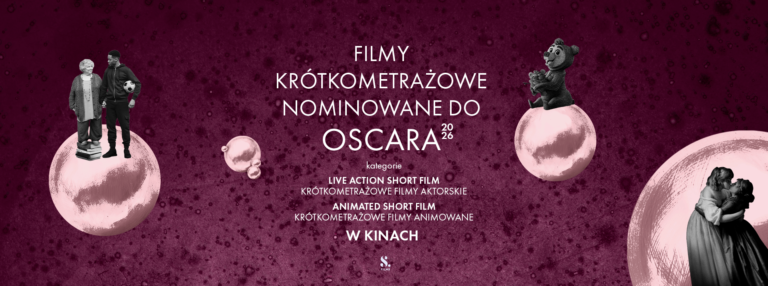

Filmy krótkometrażowe nominowane do Oscara znowu w kinach!

Oscary przyznawane przez Amerykańską Akademię Filmową należą do najważniejszych nagród światowego kina i co roku obejmują także krótkie metraże. W Polsce po raz kolejny będzie okazja, aby obejrzeć na dużym ekranie tytuły nominowane w kategoriach najlepszego krótkometrażowego filmu fabularnego i animowanego. Filmy prezentowane są zbiorczo, w zestawach, dzięki czemu podczas jednego seansu widzowie mogą poznać nie jedną, lecz nawet pięć oryginalnych historii oraz przeżyć całe spektrum różnorodnych emocji.

Program: Nominowane do Oscara 2026 Krótkometrażowe Filmy Aktorskie

Tegoroczny zestaw nominowanych do Oscara krótkometrażowych filmów aktorskich (kategoria Live Action Short Film) to cztery historie o napięciach współczesnego świata – o tożsamości, uprzedzeniach, intymności i odwadze bycia sobą. Każdy z filmów przygląda się relacjom międzyludzkim w sytuacjach granicznych, gdzie codzienność zderza się z presją społeczną, polityczną lub kulturową.

„Skaza rzeźnika” (Butcher’s Stain) to przejmujący portret mężczyzny oskarżonego o czyn, którego nie popełnił – opowieść o walce o godność i prawo do pracy w rzeczywistości naznaczonej podejrzliwością i podziałami. „Przyjaciel Dorothy” (A Friend of Dorothy) z właściwą brytyjskiemu humorowi lekkością pokazuje, jak przypadek może połączyć dwa pokolenia i otworzyć drzwi do niespodziewanej bliskości. „Dramat z okresu Jane Austen” (Jane Austen’s Period Drama) przewrotnie igra z konwencją kostiumowego romansu, wykorzystując błyskotliwą grę słów i demaskując ignorancję ukrytą pod pozorami elegancji. Z kolei „Dwie osoby wymieniające się śliną” (Two People Exchanging Saliva) przenoszą widza do świata, w którym czułość staje się aktem sprzeciwu – intymność okazuje się formą odwagi wobec przemocy i kontroli.

Wspólnie filmy tworzą wielowymiarową opowieść o potrzebie bliskości, o cenie konwenansów i o tym, jak kruche, a zarazem odważne potrafią być ludzkie relacje.

FILMY W ZESTAWIE

Skaza rzeźnika (Butcher’s Stain) / reż. Meyer Levinson-Blount / Izrael / 2025 / 26’

Przyjaciel Dorothy (A Friend of Dorothy) / reż. Lee Knight / Wielka Brytania / 2025 / 21’

Dramat z okresu Jane Austen (Jane Austen’s Period Drama) / reż. Julia Aks, Steve Pinder / USA / 2024 / 13’

Dwie osoby wymieniające się śliną (Two People Exchanging Saliva) / reż. Natalie Musteata, Alexandre Singh / Francja, USA / 2024 / 36’

Łączny czas trwania programu: 98 minut

OPISY POSZCZEGÓLNYCH FILMÓW AKTORSKICH

Skaza rzeźnika (Butcher’s Stain) / reż. Meyer Levinson-Blount / Izrael / 2025 / 26’

Samir, arabski Izraelczyk pracujący w supermarkecie w Tel Awiwie, zostaje oskarżony o zerwanie plakatów z wizerunkami zakładników w pokoju socjalnym. Wyrusza, by udowodnić swoją niewinność i utrzymać pracę, której desperacko potrzebuje.

Przyjaciel Dorothy (A Friend of Dorothy) / reż. Lee Knight / Wielka Brytania / 2025 / 21’

Spokojne życie samotnej wdowy zostaje wywrócone do góry nogami, gdy nastoletni chłopiec przypadkowo wykopuje piłkę do jej ogrodu. W obsadzie znalazła się śmietanka aktorska kultowego brytyjskiego humoru, m.in. Miriam Margolyes i Stephen Fry.

Dramat z okresu Jane Austen (Jane Austen’s Period Drama) / reż. Julia Aks, Steve Pinder / USA / 2024 / 13’

Anglia, 1813 rok. W samym środku długo wyczekiwanej propozycji małżeństwa panna Estrogenia Talbot dostaje okresu. Jej adorator, pan Dickley, bierze krew za oznakę groźnej rany, a wkrótce staje się jasne, że jego kosztowne wykształcenie ma braki w pewnych zasadniczych kwestiach nowoczesnej medycyny... Oryginalny tytuł Jane Austen’s Period Drama to satyra na „Dumę i uprzedzenie”, przewrotnie wykorzystuje dwuznaczność zestawienia słów „period drama”, co w tłumaczeniu oznacza klasyczny dramat kostiumowy, ale „period” oznacza również miesiączkę, co stanowi punkt wyjścia dla filmowego żartu.

Dwie osoby wymieniające się śliną (Two People Exchanging Saliva) / reż. Natalie Musteata, Alexandre Singh / Francja, USA / 2024 / 36’

W świecie, w którym pocałunek grozi karą śmierci, a walutą są policzki wymierzane w twarz, nieszczęśliwa Angine ucieka w kompulsywne zakupy w domu towarowym. Tam jej uwagę przyciąga beztroska sprzedawczyni. Choć czułość jest surowo zakazana, między kobietami rodzi się bliskość, która budzi zazdrość jednej z pracownic. Narratorce głosu użyczyła znana aktorka Vicky Krieps („W gorsecie”, „Nić widmo”).

Tajny agent" to jeden z najbardziej elektryzujących tytułów ostatnich lat. Nominowany do Oscara w 4 kategoriach (w tym za Najlepszy Film), zdobywca dwóch Złotych Globów, dwóch nagród w konkursie festiwalu w Cannes. Film Klebera Mendonçy Filho („Aquarius", „Bacurau"), należącego do czołówki najwybitniejszych reżyserów współczesnego kina światowego, przywołuje ducha klasycznego kina gangsterskiego. Jednocześnie brawurowo łączy wątki obyczajowe z epickim rozmachem, humor z seksapilem, nostalgię z grozą.

Film Mendonçy Filho rozgrywa się w Brazylii lat 70. podczas karnawału. Zanurzone w palącym słońcu miasto Recife jest na granicy szaleństwa: w trakcie roztańczonego święta giną ludzie, gdzieś na plaży znaleziono rekina z ludzką nogą w brzuchu, a wśród tłumów krążą dwaj zabójcy z tajną misją... Kolory i radość to tylko pozory – to czasy brutalnej wojskowej dyktatury. Marcelo, bohater „Tajnego agenta", to mężczyzna przypadkowo uwikłany w sieć politycznych i kryminalnych intryg sięgających szczytów władzy. Był uczciwy, więc stał się celem skorumpowanego systemu i teraz każdy kolejny krok może kosztować go życie. Jak ocalić siebie i rodzinę w świecie brutalnej przemocy, fałszywych tożsamości, podsłuchów i kłamstw?

Za rolę ostatniego sprawiedliwego w zepsutym do szpiku kości kraju Wagner Moura zdobył Złoty Glob, nagrodę w Cannes, ma też szansę na pierwszego w karierze Oscara. Znany z serialu „Narcos", „Elitarnych", czy „Civil War", aktor porusza się w labiryncie brudnych sekretów z lekkością i wdziękiem gwiazd starego Hollywood. „Tajny agent" jest hołdem dla kina Sergio Leone, Martina Scorsese i Francisa Forda Coppoli, do którego nawiązuje skalą i duchem. Mendonça Filho odświeża jednak i reinterpretuje kino gangstersko-szpiegowskie, wychodząc poza klisze i gatunkowe ramy. Widowiskowy, pasjonujący i przenikliwy, odsłania kawał prawdy nie tylko o przeszłości, ale i o naszych czasach.

To jeden z najbardziej zmysłowych i hipnotyzujących filmów w historii kina. Raz obejrzany, pozostaje w pamięci na zawsze. Peter Weir – twórca „Truman Show” i „Stowarzyszenia Umarłych Poetów” – tworzy kino gęstej atmosfery i niepokoju. „Piknik pod Wiszącą Skałą” to zresztą duchowy przodek „Przekleństw niewinności” Sofii Coppoli i dzieł Davida Lyncha, w którym odbija się echo nienazwanych pragnień, zagubienia i czegoś, co wymyka się prostej logice.

Rok 1900. W dzień świętego Walentego grupa uczennic z elitarnej wiktoriańskiej szkoły z internatem wyrusza pod opieką nauczycielek na wycieczkę do Wiszącej Skały, wulkanicznej formacji położonej w sercu australijskiego buszu. Tam, pod rozedrganym od upału niebem, wydarza się coś niewyjaśnionego – czas się rozmywa, przestrzeń ulega zakrzywieniu, a natura zaczyna oddziaływać na ciała i umysły młodych kobiet. Czy to pradawny rytuał? Zbiorowa halucynacja? A może, jak pisał Edgar Allan Poe: „To, co widzimy i czym się zdajemy, jest snem, który w innym śnie snujemy”? Jedno jest pewne: od tej pory nic już nie będzie takie samo.

W 50. rocznicę premiery „Piknik pod Wiszącą Skałą” powraca na ekrany kin w mistrzowsko odrestaurowanej kopii 4K, przygotowanej pod okiem samego Petera Weira i autora zdjęć Russella Boyda. To niezwykła szansa, by nadrobić seans tej ponadczasowej klasyki lub na nowo ją odczytać.

Reżyseria: Peter Weir

Występują: Rachel Roberts, Vivean Gray, Helen Morse, Kirsty Child

Gatunek: dramat

Nominowany do dziewięciu Oscarów najnowszy film Joachima Triera, reżysera „Najgorszego człowieka na świecie”, z nominowanymi do Oscara w kategoriach aktorskich Renate Reinsve, Stellanem Skarsgårdem, Ingą Ibsdotter Lilleaas i Elle Fanning w rolach głównych. Jeden z najczęściej nagradzanych i najważniejszych filmów tego roku, z muzyką skomponowaną przez polską kompozytorkę Hanię Rani.

Siostry Nora (Renate Reinsve) i Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas) spotykają się ze swoim dawno niewidzianym ojcem, charyzmatycznym, niegdyś wielkim reżyserem filmowym Gustavem (Stellan Skarsgård). Proponuje on Norze, aktorce teatralnej, rolę w swoim najnowszym filmie, który ma być jego powrotem do świata filmu. Gdy dziewczyna odrzuca propozycję, ten zatrudnia młodą gwiazdę Hollywood (Elle Fanning). Teraz siostry muszą poradzić sobie nie tylko ze swoją skomplikowaną sytuacją z ojcem, ale też z amerykańską gwiazdą, która zmienia ich rodzinną dynamikę.

Poruszająca i pełna humoru opowieść, która złamie serce, zanim znów je poskłada - Elle

tytuł oryginalny: Affeksjonsverdi

reżyseria: Joachim Trier